Background

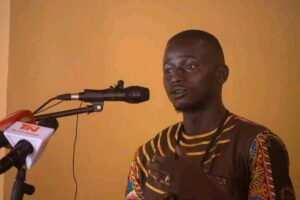

Bai Mustapha is a returnee from Libya and has experienced first hand the horrors that trafficked persons go through. He is Secretary General and co-founder of Youth Against Irregular Migration (YAIM). A Gambian national, he was born and raised in a town call Latrikunda Sabiji. He used to be a DJ and music promoter. In addition to the work he does at YAIM he also provides graphic design and PC repair/maintenance services.

Bai Mustapha graduated from Gambia Telecommunications and Multimedia Institute with an Advanced Diploma in Information Technology and Communication.

Viewpoint

AGN: Why did you decide to be part of the intervention ‘Youth Against Irregular Migration’ and when did the organisation come into being?

BMS: Several years ago I was awarded a scholarship to study in Taiwan, as there is no embassy for Taiwan in Gambia I had to go to Nigeria to obtain a visa.

I got the admission letter from a credible University. I was rejected because my former government broke its ties with Taiwan while I was in Nigeria and due to this I was rejected with other Gambian students after 3 months.

In next to no time I had spent a lot of money in Nigeria for my upkeep and in an effort to find a credible way to move forward. My funds became depleted to the point where I didn’t have adequate resources to easily return to Gambia. I had someone who would support me to Libya if I made it to Agadez in Niger. Agadez was closer to me than my country and as the situation back home wasn’t great, I decided to try ‘The Back Way’ (the irregular way of leaving Africa via Libya) to get to Europe.

I was aware trying to reach Europe via the back way was not without its perils. However, at the time I thought the greatest danger was loss of life due to drowning in the Mediterranean sea. Like many others holding on to blind hope, I didn’t think such a thing would happen to me.

My experience and those recounted and that continue to be highlighted by others is testimony to the fact there are a multitude of perils associated with the journey over land, ranging from repeated rape, extortion, torture, enslavement, forced sex work to murder/organ harvesting. That is by no means an exhaustive list.

I began my journey from Nigeria by travelling via the Republic of the Niger, through the desert to Libya. On arriving in Libya I was caught by the police and remained in prison for 4 months with other compatriots/ Africans. I was surprised at the many number of young Africans who were being detained in the same facility.

I soon came into contact with other Gambians and we were able to group together. In comparison to some of the people from other African countries we were fairly united. You would think that in such an environment where many people had experienced horrific things, people would band together. While to some extent that was the case, there were still others that formed themselves into gangs, usually along the lines of nationality and/or ethnicity in order dominate and extort for their own benefit.

At around about my third month in detention, staff from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) began visiting and offering repatriation. Although the conditions we were being detained in were deplorable, and some people were ill and did die amongst us, not everyone jumped at the chance to be repatriated, for some, there was a general reluctance to accept IOM’s offer because of the awareness of the realities that had led us to leave our respective countries in the first place.

Like myself, many had experienced unbelievable horrors to get this far. People recounted stories of witnessing people they had been travelling with being raped before their eyes, some had also been on the receiving end of this. A number of females were pregnant as a result. Others had been badly beaten or witnessed a sick person falling off or being evicted from the same vehicle carrying them while travelling through the desert. Such people would almost certainly die as a result of being abandoned like that. There were corpses littered along the way. Some had experienced people being murdered on a whim right before their eyes.

For those able to raise funds, it was possible to regain ones freedom and continue the journey. I had to weigh the possibility of doing this against my main reasons for not wanting to return which are as follows;

- We the youths are the highest percentage of the population, and subsequently the highest number that are unemployed or under employed. There is an acute scarcity of meaningful employment in our country.

- Due to a lack of capacity there are far more students eligible to study at university than there are places. This leads to all sorts of undesirable issues and generally makes it even harder for people from poorer backgrounds to gain entry on merit. As a point of note, while academic qualifications are the most viable method for social mobility, foreign qualifications are typically valued higher than local ones.

- Inequality is rife between socioeconomic groups. Skilled and semi skilled workers are not respected, there, marginalisation leads to exclusion from processes that allow for social mobility. It’s totally unfair to expect people to work just as hard if not more so and yet remain poor or on the breadline.

- In answer to your question, the organisation was formed by those of us that were detained in Libya while we were actually there and uncertain whether we would all make it out alive. Founding it was bourne out of our individual/collective experiences and the desire to deter our compatriots from experiencing the terrible things we had faced. We began informally in 2017.

AGN: One can never trivialise the horror of human trafficking irrespective of the scale. It appears this crime has mushroomed, do you have any indication as to when more people began to be ensnared in this horror?

BMS: This activity has been going on for more than 4 decades now but it started to get out of hand around 2005 due to the challenging political climate in The Gambia. People started using the back way in earnest after the death of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. Things exploded in 2015/ 2016 as the Yahya Jammeh political era was nearing its end.

It was observable that those with people abroad who were receiving remittances had a better standard of life, this acted as a motivational factor for people to leave. Also, increasingly those commercially involved in the process e.g. providing transport along the route, would come touting for interested persons.

AGN: Is there a particular part or parts of your country where survivors associated with this crime is highly prevalent and why is that?

BMS: It manifests around the country, however, the general view is that the North Bank Region which is in the north of the country as well as the Upper River Region in the eastern part of the country, record a higher number of returnees and deaths. Most of the people I met during my journey and subsequently the returnees or family members/friends of people who have left Gambia through irregular migration, as well as the highest number of deaths recorded as a result of the visits I have made to different parts of the country, are in line with the general view.

Let me provide you with some examples.

Njaba Kunda, a place in the North Bank Region recorded a loss of over 100 youths during one of my visits.

Dampha Kunda, a place in the Upper River Region lost 11 people in one compound in one instance.

In 2019 between November and December, boats were sailing from Gambia (North Bank Region) to the Canary Islands, and these boats could carry up to 195 people. On one occasion around 85 people died including a mother and baby of less than one year old.

AGN: Do you feel you have adequate data to enable you fine tune your operations?

BMS: I am inclined to say no. As an organisation we do collect data but our ability to do so is limited.

AGN: The nature of this crime means reliable data can be challenging to come by, what more would you like to be done with regards to the gathering of locally derived data on this issue?

BMS: I would like to see our government doing more in terms of robust gathering, analysis and reporting of data. For comparative purposes we are more likely to refer to external bodies such as IOM rather than our own government’s reports. The caveat is that we are aware that as community based operators, some people open up us to in a way they may not necessarily do when responding to international bodies, even if such bodies utilize Gambians to collect their data. This can skew things and make the picture less clear.

AGN: What would you say are the key factors that lead to people seeking irregular migration as a means to an end?

BMS: As far as my country is concerned there is a dearth of meaningful opportunities for growth and for people to actualize themselves.

AGN: Do you experience any push back among the general populace when you seek to raise the alarm over the dangers of irregular migration?

BMS: Yes, however, the size of our movement and its varied connections to the communities we serve makes our message more believable. Some people are prone to being sceptical about interventions from foreign owned organisation and argue that because they are highlighting stories of people who have failed it doesn’t mean they will.

When our organisation of over 30 people say no we experienced these very things and they see us supporting and spearheading self help initiatives it give us greater credibility among the local populace. We are well aware that sensitization will not make a great deal of difference without facilitating meaningful opportunities that enable people to develop and grow.

AGN: Obviously there are a range of factors associated with a given individuals circumstance, in terms of your experience, where an individual has not sought irregular migration voluntarily, are agents typically strangers or known to the victim/ victim’s family e.g. relatives?

BMS: Generally, initial agents tend to be people known to family members or someone that the victim is aware of rather than a complete stranger.

AGN: We hear of instances where people who are returnees and are or have been trained and possibly assisted to set-up a venture, still seek to drop everything in order to utilize irregular migration to leave Africa as soon as an opportunity arises, have you come across such instances, if so why does this happen?

BMS: Fundamentally, I believe short-termism in terms of the solutions provided is the reason behind such behaviour. Some are just not convinced they can flourish long term here. Many of the solutions provided are like a little sticky plaster over a gapping wound. It’s not enough just to have a job with no prospects. People have aspirations, it is only natural that they seek out ways to actualise themselves.

There are also a number of other pressures that can contribute to a person reconsidering their position.

The training provided by some of these agencies is not extensive and often doesn’t cover additional expenses. It does not always inspire confidence.

Gender can also play a part. There was a member of my group who was a returnee, she would visit schools and other places telling her story and advising people not to utilize irregular migration channels, before too long she had again utilized the approach to leave the country.

Part of the reason for females having a harder time is that there is a stigma associated with the notion many would have been forced into sex work and/or raped. This can lead to a sense of shame. Allied to that is the general stigma of returnees being seen as failures. However, this aspect is beginning to change because so many people have become returnees and there is more awareness around the issue.

It’s one thing to be mean to someone who is not related to you. The greater prevalence of returnees has increased the likely-hood of people being related to one. This is helping to moderate how others perceive us.

AGN: Do you face resentment as a returnee?

BMS: Yes. What we have done is illegal. Some people are not happy that resources are being allocated to us when there are plenty of people who are struggling and have not done what we have done.

Our organisation offers support to both returnees and the general populace. We don’t want to encourage the belief or give rise to a system that provides privileges to returnees at the expense of everyone else as that would be counterproductive from discouraging people to try. Providing support to returnees and poor people in general helps to temper resentment.

AGN: What changes would you point to in the way things are done now in comparison to how they were done when you were repatriated in 2017?

BMS: Returnees who have been traumatised e.g. victims of rape who in some cases have gone on to birth a child whose father is unknown, to those who have experienced murder, sometimes multiple times, or who have been maimed and/or enslaved and so on. Such people would benefit from different types of support, depending on their needs.

In 2017 I was among 171 Gambians repatriated from Libya, ours was the 2nd chartered flight that had been organised. On arrival back at our airport in Gambia, no government representatives/service professionals were there to receive us and no orientation was provided.

We were left to just go back to our families without any health screening or counselling. In this regard things have changed quite dramatically since then. Temporary accommodation is now provided as well as a whole range of support services.

AGN: In terms of the long term, while there are governments that are doing their bit, civil society/non-state actors are also very dynamic in addressing this issue; through skills acquisition/training, education, entrepreneurship and so on, having said that there are only so many skilled/semi-skilled workers and graduates an economy can absorb.

A global economy that does not operate on a level playing field is not going to right itself because of the hardships faced by Africans or black people across the globe in general. As long as even a menial job in parts of the world outside Africa derives greater economic value for most Africans, leaving the continent for such places is unlikely to lose its appeal.

Unemployment and underemployment are very high in Africa across the socioeconomic spectrum. Do you feel the approach of training and assisting individuals to set up small businesses will yield a long term strategic benefit that will make a pivotal difference?

BMS: I don’t believe the current approach is adequate and I have no confidence of a material change occurring in future if things stay the same. While the footprint of international/local aid organisations has grown, the long-term plight of returnees has worsened. The focus should be on quality rather than quantity of trainees. This would of course leave a question mark over what happens to everyone else who is not put through a training programme.

I also feel apprenticeships should be encouraged rather than just a focus on short term training.

Gambia imports a high percentage of food despite having suitable land, climate and environment. I believe far more should be done in terms of orienting programmes towards the agricultural sector.

I am reluctant to thank donors who I don’t deem to be worthy. I do appreciate that IOM’s intervention has saved lives and helped a vast number of people including myself and I am certainly thankful for their work in this area.

Our organisation has also received funding from some of these organisations, including IOM for a range of projects and it is appreciated.

However, the current arrangement seems to benefit the aid industry far more than it does the overwhelming number of people it is supposed to serve.

I do appreciate that the voluntary sector cannot undertake the role of the government. I am aware different organisations will no doubt have specific constraints and compromises that have to be made, however I am definitely certain the balance is far from right.

The tendency is towards short term intervention rather than support that will yield long term benefit for recipients and hence set them on a path to making something of their lives rather than eventually falling by the wayside because structurally the deck is stacked against them.

This is the fundamental problem. Many in the aid industry are well compensated for their efforts and/or others can use the voluntary experience they have gained to advance themselves in some way, however, the number of poor and destitute Africans is growing exponentially.

We as poor Gambians/Africans cannot sit idly by while our poverty forms the basis of rewarding others far more than it leads to any meaningful transformation for the majority of us.

People like me are in a difficult position. Our organisation receives some support from donors but we are aware we are just a small cog in the greater scheme of things, existing in an unfavourable landscape. For obvious reasons people are not eager to speak up.

AGN: What have you realized about life in Africa since returning from Libya?

BMS: After returning I realized that Africa is blessed with potential resources, especially my country.

I realized that to a certain extent our problems are due to poor leadership because the same reasons that push us to migrate irregularly are still there, even after government’s change.

I strongly believe that Africa will rise and that we are the ones to make it happen… We cannot be running away from our destiny.

AGN: Is there anything else you would like to add

BMS: It is hard to quantify in more precise terms how successful our efforts are. Our organisation is able to travel around the country and I am encouraged when people feedback to say they never accepted the things they heard before until now they are hearing it from people they can identify with, who have seen what it is like with their own eyes.

Having said that, I feel this issue requires a collective effort. It cannot just be left primarily to a few organisations.

In some cases, the choices people make who are en route or have reached their destination can further be complicated due to the expectations and demands of family members back home who would have invested in the person undertaking the journey. At times emotional pressure is applied for money by family members who haven’t been supportive in any way shape or form. This can often lead to people engaging in illegal activities because of the harsh realities they face when they realise that to make ends meet, get ahead and send money back home, is far tougher to do than they imagined it would be.

On an individual basis I struggle to get support from family members or many of those closest to me. They see me on TV sharing platforms with members of the government, dignitaries e.t.c and assume I am well rewarded. While other attendees will usually have arrived by car I may well have walked many miles to get to the same place. It is indeed a constant struggle.

As is the case with my colleagues, I don’t do this work in order to generate wealth so I don’t pay any attention to the overly assumptive comments sometimes aimed at me. Despite our efforts, some people are still determined to hold on to their assumptions in relation to this issue. What I have just said highlights that.

It is what it is. We will keep on.

AGN: Bai Mustapha, it’s been a revelation to hear your comments. Please keep up the work you are doing. Thank you.